Lessons From the Game: The Best Loss of All Time

The Story of the 1942 Boston College Football Team

One thing that’s almost universal to coaches is that they hate to lose. Very rarely will you find a coach that is OK with taking a loss. Legendary Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne famously said, “Show me a good loser and I will show you a failure”, and a lot of coaches have that mindset that it’s never OK to lose.

There are exceptions. One that comes to mind for me is Tyson Moser, the football coach at Idaho’s West Side High School. Moser not only doesn’t mind losing in the regular season; he actually prefers it because it makes it easier for his team to focus on its real goal of winning a state championship. His Pirates learn what they did wrong, fix it and refocus. It’s worked well for them; West Side has won seven state titles in the past 15 years.

Above the high school level, that’s a lot harder to find. Most coaches wear the claim that they hate to lose as a badge of “honor”. When Notre Dame coach Micah Shrewsberry was at Penn State, he routinely smiled as he described himself as a bad loser. Former Missouri football coach Gary Pinkel would bristle at the idea that his team might not enjoy a win because they didn’t play very well, saying forcefully that “You enjoy winning”. (The fact that I can’t remember who the Tigers played that day says that wasn’t a win to write home about.)

One of the only times I saw a college coach admit to feeling good after a loss came from Missouri volleyball coach Wayne Kreklow. Missouri had just played and lost a four-setter to Nebraska, and if you know anything about college volleyball, you know that the Huskers are volleyball royalty. The Tigers had been in every set and even taken one off the top-ranked team in the nation.

To Kreklow, that was a sign that his team had a chance to make a run in the NCAA tournament, which it did. Missouri ended its year in the Elite Eight, its best finish in school history. And after that match, Kreklow openly admitted that he was happy with his team’s showing and that it was as good as you could feel after a loss.

While I give him credit for that, he’s wrong. Because that loss pales to the 1942 Boston College football team’s loss to Holy Cross — a defeat that literally saved the Eagles’ lives.

Boston College in 1942

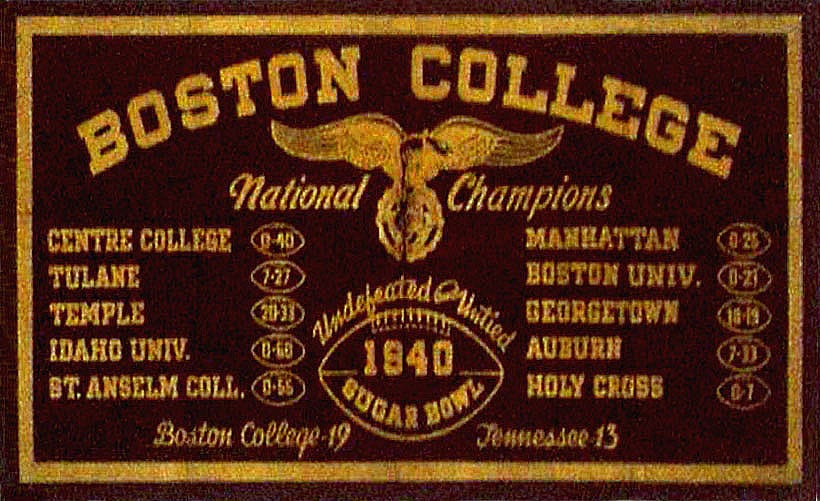

In 1942, Boston College was a powerhouse on the gridiron. The Eagles did everything well, outscoring their first eight opponents 249-19. Fullback Mike Holovak was one of the hardest runners in the nation and finished fourth in the voting for the Heisman Trophy. The Eagles had a quality quarterback in Ed Doherty and an All-American wide receiver in Don Currivan.

Their defense might have been even better. BC had the top rushing defense in the nation, allowing 48.9 yards per game. The pass defense was also incredible, allowing just 82.9 yards per game. (Teams weren’t throwing the ball anywhere near as often in the 1940s).

You get the picture. This was a championship team from top to bottom. And Sugar Bowl officials couldn’t wait to match the Eagles up with Tulsa.

The pairing made perfect sense. The Golden Hurricane had the nation’s top scoring offense. If anyone could handle the fearsome BC defense, it figured to be Glenn Dobbs and Tulsa. All the Eagles had to do to earn the Sugar Bowl bid was beat archrival Holy Cross and its single-wing offense, considered to be on the way out of the sport as an antiquated offense. (It wasn’t, but that’s a story for another day.)

Everything looked straightforward. Until it wasn’t.

The Game With Holy Cross

Most people don’t remember that Holy Cross used to have a big time athletics program. Craig Meyer just touched on Holy Cross’ offer to join the Big East in 1979, which speaks to how strong the Crusaders once were in sports. These days, Holy Cross participates in the Patriot League, and its rivalry with Boston College is non-existent.

BC and Holy Cross are separated by 42 miles of Interstate 90, but they’re a lifetime apart in athletics. Boston College now plays in the ACC and has been a fixture trying to compete at the highest levels of sports. Holy Cross stopped awarding athletic scholarships for a time when it joined the Patriot League. But in 1942, these schools were rivals and peers, and this was the big game in Massachusetts.

The Crusaders knew they were better than their record. The thing about the single wing is that it’s a tough offense to figure out. It takes the offense time to learn it, and it’s almost impossible for a defense to learn how to stop it. I should know; I grew up in Virginia, where Mickey Thompson and Stone Bridge High School have been bludgeoning teams with the single wing since 1998. Every year at Liberty High School, we knew that if we wanted to go anywhere in the playoffs, we had to stop the single wing.

Back in 1942, though, almost everyone ran it. The main exception was the Chicago Bears, who had just steamrolled Washington 73-0 in the 1940 NFL championship with the T-formation. And Boston College coach Denny Myers, a former Bear, had installed the T at BC.

Most teams didn’t know how to defend it. One of the rare exceptions was Holy Cross. The Crusaders had a secret weapon in assistant coach Hugh Devore. Devore had played his college football at Notre Dame, where he served as the Fighting Irish’s defensive captain under coach Hunk Anderson.

Where was Hunk Anderson in 1942? Coaching the Chicago Bears in place of George Halas. Halas had stepped away from the Bears to re-join the Navy in World War II, and Anderson took the reins. So when his old captain contacted him to ask how to stop the T-formation in preparation to face Boston College, Anderson gave Devore and the Crusaders the Bears’ secrets.

The Eagles never stood a chance. Holy Cross scored first and never trailed. The Crusaders allowed a touchdown to Currivan on the Eagles’ first drive, but after that, the lessons from Devore and Anderson began to kick in.

Holy Cross ended up forcing 10 turnovers, intercepting six passes and forcing four fumbles. The Crusaders’ defensive domination was so complete that they found themselves facing short fields at Fenway Park all day. For the game, Holy Cross notched just 335 yards of offense despite scoring eight touchdowns.

When all was said and done, the Eagles’ No. 1 ranking lay in ashes, courtesy of a 55-12 loss to the Crusaders. The result was so unexpected that newspaper editors initially didn’t believe the halftime score across the wires. Back in 1942, information came via Morse code, and any mistake with Morse code can throw off the entire meaning. So when the halftime score of 20-6 came across, editors assumed that their writers had goofed and meant to say BC led 20-6. When the message came back a second time, the college football world began to realize what was happening.

Sugar Bowl officials scrambled out of town. The Eagles wouldn’t be going to New Orleans. They also wouldn’t be going out in downtown Boston. The team had planned to celebrate their undefeated regular season and their Sugar Bowl bid that night at the Cocoanut Grove, one of the most popular nightclubs in Boston. But the Eagles were so embarrassed by their performance that they cancelled the celebration and went back to campus.

The next morning, they were thankful they had.

The Cocoanut Grove

The Cocoanut Grove name is infamous today because of what happened that night, November 28, 1942. But in 1942, it was one of the most well-known spots in Boston. And if all had gone according to plan, it would have been the place to be for Eagles fans that night.

But the building had serious problems that would be unthinkable in modern times. It only had one exit at the front, a revolving door. It had other exits, but they were only known to employees. Several of the exits were locked from the inside, and the Grove was full of flammable decorations that gave the appearance of the Caribbean.

On that fateful night, the fire might have come from one of two sources. Either a busboy lit a match while trying to replace a light bulb, or an electrical malfunction lit a spark. Either way, the fire quickly consumed the flammable decorations and headed straight for the main area.

The Grove had another problem: it was severely overloaded. Its building codes could comfortably hold about 400 to 500 people; around 1,000 people jammed into the Grove that night. The combination was too much. People tried to get through the revolving door, which jammed helplessly against the crowd. Many had nowhere to go and were instantly overcome by the flames and the smoke.

Those who made it outside quickly found their lungs unable to adjust to the Boston night air of November. In all, 492 people lost their lives that night, the deadliest nightclub fire in history.

And the Boston College football team was nowhere near it, safely back on campus because it had lost its biggest game of the year. The Eagles would live to play in — and lose — the Orange Bowl against Alabama. Had they won that game against Holy Cross, it’s highly probable they would have lost their lives that night.

Accepting Defeat

One of the hardest things in life is to accept that some things won’t work out. Defeat is a difficult experience, but it’s never permanent. There is always another day for things to go better, another opportunity for you at work, another possibility to rebuild relationships.

Defeat is of course disappointing, but it’s important to remember that sometimes, it happens for a reason. It could be that an opportunity wasn’t what it was supposed to be, or that you’re going to get something better than what you had expected. It could also be a chance to learn for the future.

For the Boston College football team in 1942, it was literally a life-saving loss. Obviously, they would have preferred not to get humiliated on the football field, but given what could have happened, it was a small defeat that didn’t mean that much.

And that’s why it was the best loss of all time.

Really liked this. Great story about the history of the game and your reflection on life.